Fifteen August is easily the most important date in India’s modern history, invoking liberation and horror simultaneously because freedom was birthed in brutal violence. Dates focus the direction of a nation’s memory and temporal rhythm. My favourite Indian date remains 26 January, when India was anointed a republic and democracy. And not least because this was a date with history that was chosen and enacted entirely by Indian leaders rather than the British Raj. More than individual dates, it’s the horizon of time that frames the regime of history. As the brilliant historian Christopher Clark’s recent book Time and Power demonstrates, time is a political category that orients regimes because it empowers political narratives. Each political regime thus is marked by a distinct texture and experience of time.

History, ironically, has less to do with the past and more with occupying the future. In the case of modern India, history and its writing has been crucial to the imagining and working of nationalist and democratic politics. Almost all our significant founding figures wrote history. History became a template to express and project views of India’s future. Those who did not indulge in inking their views nevertheless held divergent views on the past. The contestations have thus been not only about the past, but also on the relative value of history for politics in the here and now. In fact, India’s ideological distinctions cannot be mapped only from the many histories figures such as Jawaharlal Nehru or Vinayak Damodar Savarkar published. In short, the question of whether the past offered an instruction manual for political action in the present or whether history (keep original for clarity) was a morality tale, divided them equally.

Also read: Savarkar never offered a clear definition of Project Hindutva. A new book shows that again

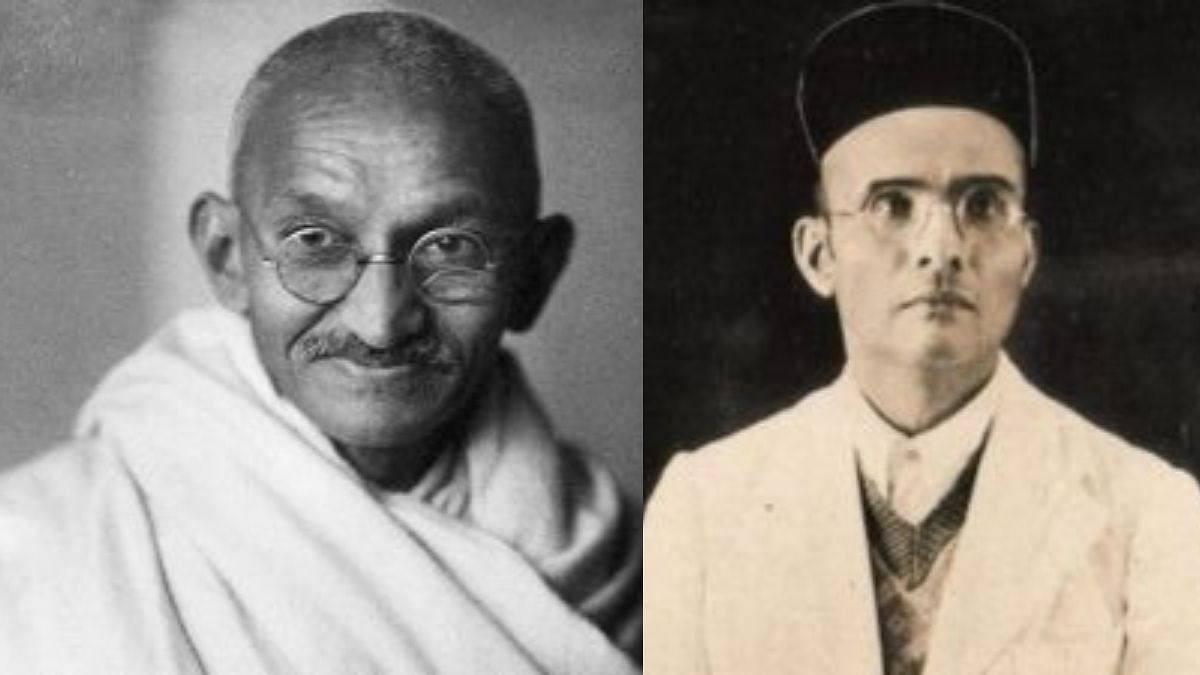

War/peace: Savarkar/Gandhi

As the most influential and consequential Indian political actor, it is striking that M K Gandhi had no time for history. On this too, he was a total outlier and strongly at odds with all his political contemporaries, whether it was his tormentor Winston Churchill or his protégé Nehru — both internationally best-selling historians of their day.

Gandhi took a dim view of history. This was because, as he often noted, history was equal to violence. Precisely because nonviolence was ordinary and that nourished the conditions of life, it left little to no record. If you glance even briefly at his 1909 political manifesto Hind Swaraj and any subsequent writings or lectures that run into a hundred-plus thick volumes, Gandhi is particularly good at centrally staging the importance of individual agency with smatterings of one-liners and quips from the epics and even religious sayings that highlight its necessity. No proof is offered, nor any support taken from the recent or remote past. For Gandhi, India’s long-standing identity was best understood and projected as an evacuation from history. Gandhi’s anti-historical ideas were as radical as they were plain. Privileging both the everyday and the eternal notion of time enabled him to create a unique and profoundly consequential ethical politics that vexed both imperialists and some nationalists in equal measure.

Gandhi’s political nemesis in Savarkar was in no small measure owed to this fundamental difference on the valuation of history as violence. A prolific historian, Savarkar singled out India’s stagnation and subjugation as an outcome of nonviolence. In his final work Six Glorious Epochs published in 1963, a couple of years before his death by suicide, Savarkar singles out the dynamic power of violence. India’s identity over the course of two millennia is charted by six consequential confrontations and primarily Buddhism and Islam. India is converted into a battlefield. As a declaratory form of history, Savarkar dons the mien of a military historian. Savarkar’s aim in touring the past is to signify the work of conflict in creating new forms of identity and attachment. History then was not so much proof of Hindutva’s longevity. Rather, as a brand-new political idea, history offered the likely conditions of Hindutva’s fulfilment. In this sense, despite being its founder, he has been at odds with Hindutva’s zealous followers because he dismissed the epics, Puranas or any claims to deep antiquity for Hindutva. If anything, Savarkar aimed to rouse the reader to think of history as a political intervention in the present that would emerge victorious in future conflicts.

Also read: Savarkar’s Hindutva wants obedience. But obedience has never helped economy

Political futures foretold

Savarkar’s Six Glorious Epochs was a direct response to Nehru’s best-selling 1946 account Discovery of India. Written in prison, Nehru’s blockbuster charted the same two millennia of India’s past as Savarkar. But to powerfully proclaim and prosecute a new form of nationality in world history. While Europe and the West had violently made linguistic, ethnic and religious uniformity the basis of nationality, the history of India for Nehru offered a new political principle. Diversity became the byword for India’s spirit that had remained strong and steadfast despite the subjugation. India for Nehru offered the most valuable instruction to the world and as a powerful antidote to the violent history of the last century.

Though entirely opposed, Savarkar and Nehru both deployed history to conjure a future. The anticipation of the future through historical writing is a singular hallmark of modern India’s political thought. For a century now, political ideas in India have primarily been conveyed in the historical register. This prognostic or futuristic form and disposition towards time distinguishes the historical writings by political actors from that of say the professional historian. Though fundamentally opposed, Savarkar and Nehru’s works had the markings of a utopia, however positive or negative.

Strikingly, and unlike both Nehru and Savarkar, Ambedkar took a view not too far removed his anti-hero, Gandhi. In surveying the momentum and arguments for and against Partition, he too toured the thickets of the past. The inability to forget the past, Ambedkar wrote, had precisely led to the violent conflict between Hindus and Muslims in the present. A degree of forgetfulness, contra Nehru and Savarkar, was essential for the forging of India’s nationality.

The wars of history are in effect wars to control the future. Neither remote nor proximate, history is the present and active template and a vehicle for conveying and enacting political ideas. Strikingly, unlike all political warriors and actors, Gandhi abandoned history to face the future fearlessly to remake India. In so doing, Gandhi above all, made history.

Shruti Kapila is Professor of Indian history and global political thought at the University of Cambridge. She tweets @shrutikapila. Views are personal.

(Edited by Anurag Chaubey)

Source: The Print